In my previous post on The Value of ITF Patterns (Part 1), I focussed on their intangible contributions: firstly, the patterns act as a vehicle for the dissemination of Oriental Philosophy, Korean History, and Korean Culture. Secondly, unlike Karate's kata where their development was primarily functional, the ITF patterns were from the very beginning intended to have an aesthetic quality. They are therefore a type of kinetic artwork, poetry in motion, a martial dance. (Another intangible value of the patterns that I alluded to—but did not elaborate on, as it is speculation—was that the patterns could possibly have an ascetic function; in other words, they could potentially be used meditatively to assist in spiritual growth.)

I hope to discuss the more tangible value of the patterns soon. Particularly, I want to focus on the “kinaesthetic” training value of patterns. However, before I do that, it is important to address a misconception that one of the main purposes of the patterns is physical conditioning.

Is a Chief Purpose for Doing Patterns the Physical Exercise? -- Not in ITF

The idea that a chief function of pattern practise is aerobic exercise, strength training, and so on, is mistaken—at least as far as the purpose of patterns in ITF Taekwon-Do is concerned. This misconception regarding the ITF patterns are held by non-ITF practitioners not familiar with the ITF pedagogy, but strangely also by some ITF practitioners as well; maybe because vigorous training of the patterns does indeed cause exhaustion and can be good aerobic exercise.[1]

Recently Dan Djurdjevic, one of the martial art bloggers I particularly respect, discussed “Forms: their core purpose”. For him, as I am sure is the case for many martial artists, a principle value of the forms / patterns is physical exercise.[2] He mentions for instance how in the forms the stances are deliberately low and “normal stepping,” which is impractical in actual fighting, are deliberately employed to create “load”, i.e. it is made difficult on purpose. In other words, a big part of form training is for their value as aerobic exercise and strength training—to condition the body.

Body conditioning is not a primary reason for pattern training in ITF Taekwon-Do. In his description of the patterns General Choi Hong-Hi, the principle composer of the patterns, mentions certain tangible things that one can gain from their training:

“Thus pattern practice enables the student to go through many fundamental movements in series, to develop sparring techniques, improve flexibility of movements, master body shifting, build muscles and breath control, develop fluid and smooth motions, and gain rhythmical movements” (ITF Encyclopaedia, Vol. 8, p. 13).

To “build muscles” may be considered body conditioning, but it is clear from the quotation that it is one of many points and is actually grammatically linked with “breath control”. From this, the type of muscle building that occurs in the practise of patterns in ITF does not seem to be focussed on fitness and strength training—an important value espoused by my friend Dan.

When the ITF patterns have body conditioning in mind, their moments are often very conspicuous (and dreaded by practitioners). Obvious examples are the slow motion kicks some patterns such as Moon Moo. Since these kicks are deliberately done in slow motion, they clearly have no practical value—you will never kick somebody in slow motion in real life. The value of these particular movements are obviously for strengthening the leg muscles and developing balance, but these obvious conditioning actions are sporadic.

(There is also, of course, an aesthetic value to the slow motion techniques.)

The Patterns Are Not Dallyeon

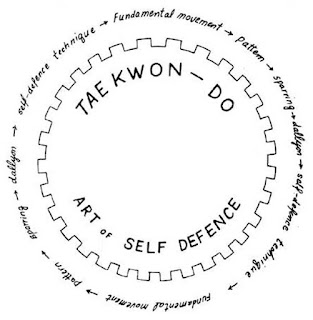

The different components of physical training of ITF Taekwon-Do is illustrated in the ITF Encyclopaedia as a composition cycle, made up of five elements: fundamental movements, patterns, sparring, dallyeon, and self-defence.

|

| "Cycle of Taekwon-Do" Source: ITF Encyclopaedia, Vol. 1, p. 238. |

Dallyeon is the only element in the cycle that is not translated from Korean into English. So what is dallyeon?

|

| One type of "dallyeon" -- Image Source |

With regards to physical training, dallyeon refers to all types of training that will “temper” the person, including general fitness, stamina and strength training, the hardening of the attacking and blocking tools, flexibility training, reflex training, line drills, partner drills, combination drills (kicking-and-punching combos), sparring and so on. Dallyeon should also be understood to include training of the mind and character.

|

| South Korean soldiers engaging in dallyeon. Training in the snow requires both physical and mental endurance. Image Source |

|

| A comparison of an ITF Walking Stance (above) and a Shotokan Karate Forward Stance (below). Notice that the ITF stance is not as deep as the Karate equivalent. (Image Source) |

Dan is astute and correct in his observation that ITF patterns have lost their “load”. If this was the case for another martial art where patterns have a conditioning function it would indeed be a serious loss, as Dan rightly points out. However, this is not a major purpose for the patterns in ITF Taekwon-Do. In ITF Taekwon-Do conditioning is found chiefly in dallyeon.

The Way We Move in the Patterns Are Not the Way We Move in a Fight

In his posts “Forms: their core purpose” and “Sine wave vs. the core purpose of forms” Dan's main focus is on the value of the forms to provide a “dynamic context”, something I very much agree with and hope to write on in a future post regarding the value of patterns. One critique Dan has of the sine wave motion and it's manifestation in the patterns is that while the patterns make for a “dynamic context”, the slowed down characteristic of the sine wave motion causes unnecessary “dead time”. My response to this is twofold:

First, the sine wave motion is not ever present in ITF Taekwon-Do. Although it is a very conspicuous part of the patterns and some fundamental movements, it is not employed to the same degree in other parts of the art. And since the patterns are not to be understood as “a template for fighting” in ITF Taekwon-Do, the presence of the strong sine wave motion in the patterns is not a serious issue, because the stepping needed for fighting (in the meele range) are actually practised elsewhere in the system, like in some line drills and the higher forms of step sparring (dynamic context drills), semi-free and free sparring, and self-defence training.

Secondly, Dan explains the “dead time” as that time in natural stepping between when you start to initiate movement (i.e. push with the rear leg) until the time it takes your body to actually transfer momentum forward. He contrasts this with drop stepping: “The drop step is the very opposite of the natural step in that your front foot initiates movement not your back. / When you lift your front foot you should notice something very different from natural stepping: you start to fall forwards immediately. There is absolutely no delay between your foot lifting off the ground and your forward force being exerted.” The interesting thing about the sine wave motion when correctly applied to natural stepping is that it actually creates forward momentum from the get-go just like the drop step. I explain this peculiar motion without movement in another post..

In summary, the patterns are not truly dallyeon-of-the-body; in other words, their function is not really aerobic or strength training. Having said this, the mere act of “going through the motions” does have an exercise value. You can get quite exhausted from pattern practise. Still, in its essence, the chief purpose is not dallyeon. Also, the patterns are not viewed as “templates for fighting” in ITF Taekwon-Do. Therefore, possible “dead time” caused by the slowness of the sine wave motion in patterns is not a major concern for the ITF practitioner, because we do not consider the patterns the platform where we learn how to step for real fighting (in the melee range).

In a future post I will discuss what I consider to be the kinaesthetic principles that the ITF patterns aim to teach us. Until then, make sure to read Dan Djurdjevic's “Forms: their core purpose”.

Footnotes:

1. Just because a chief function of patterns is not dallyeon (conditioning) doesn't mean that conditioning doesn't occur. All movement will translate into some level of conditioning. In Wushu (modern Chinese kung-fu) the main purpose is aesthetic performance, however the physical exersion required of the Wushu forms makes it impossible to downplay the value these forms have on body conditioning. In Wushu one cannot seperate the aesthetic goal with the strenuous physical exertion. My argument is, however, that conditioning is not a main purpose in ITF Taekwon-Do. Or put differently, although physical exercise is inevitable during pattern practise, that is not its main goal, to such a degree that one can separate the goal of the ITF Taekwon-Do patterns from physical dallyeon.

2. Note that the main idea of Dan Djurdjevic's post is not that forms are primarily used for conditioning, that seems to be a secondary dual function. For him the main purpose of the forms are to provide a dynamic context for practising fundamental movements.

3. I don't think that dallyeon-of-the-body truly occurs in the patterns, but there is a strong case to be made for some type of dallyeon-of-the-mind that could occur through pattern training, seeing as patterns are often considered a form of mobile meditation.

18 comments:

Very good reply Sanko. I would respond with observations in 2 parts:

First, the moment you practise techniques you are, in a sense, "conditioning" the body. For those who have never done front kicks, they are very, very hard. Beginners who are otherwise fit (for running, bench press, squats, rowing, high jump, cycling, surfing – you name it) often emerge from a fairly simple lesson of kicking drenched in sweat. Their bodies simply aren't "conditioned" to it.

So my view is, unambiguously, that there is always a "conditioning" element to any form/pattern. It needn't be the kind of conditioning one does in a gym: it is merely the necessary conditioning to do what you need to do (step, kick, punch, etc.); to get your muscles accustomed to firing in a particular way and to get your brain synapses mapped accordingly.

And I'm afraid your description of karate stances is incorrect. Yes, it is true of, say, shotokan karate – but not of many other styles. In karate there are many, many who use higher stances of exactly the kind see in taekwondo. In fact, this was the norm in Okinawa before Gigo Funakoshi introduced the extremely deep stances that now characterise shotokan and its offshoots. Even in the Chen Pan Ling system we use higher stances of the "taekwondo kind".

But higher stances don't mean that they are so much "easier" that your body doesn't need "conditioning" to them in the sense to which I refer above.

More importantly, it also doesn't mean that it is "easy" to move from one stance to another with no height differentiation. It is actually quite hard; the relative "height" of, say, a particular forward stance doesn't change this – you still need to teach your muscles how to move efficiently from stance to stance. This is the purpose of the dynamic context. Yes, it's even harder to do this if your stances are ultra low, as per shotokan, but that is another issue entirely.

Second, I'm afraid I cannot see how sine wave could possibly improve your speed from the "get go".

After more than 3 decades of cross-referencing the external and internal arts, I see the very scientific way in which the latter deal with "dead time" as one of their biggest strengths. I will shortly explain exactly how each of the 3 arts achieves this in its own unique way (I haven't had the time to write my article on this subject yet, but you can get some idea from this video).

In the tkd forms I've seen, the "sine wave" is absolutely unlike, say, the "drop step" of xingyi. Rather, sine wave utilises a "load" by rising. Sure, once you are "up", the next part might benefit from gravity and increase speed. And once you are on a "on a roll" (with multiple steps) there might even be some benefit too. But in the initial "natural" step, nothing changes the fact that you go through the "dead time" zone. By contrast, in xingyi's "drop step" you instantly exert force. Yes, the "drop step" of your front leg extending is usually then followed by a full "natural" step (ie. you get "on a roll") – but by then you should already have your opponent on the back foot and your exposure to the dead time has been minimised.

While you say that taekwondo patterns have some reason for using the sine wave, I can't help feel that whatever it is, it detracts from their basic core reason; to put techniques into a dynamic context; one that maps the synapses for optimal movement and that "conditions" the muscles so that they can do the work necessary to achieve this.

All the best!

Dan

By the way, my video above deals with "over extension" but this issue and "dead" time" are, for all intents and purposes interchangable: at full extension you face the prospect of dead time.

Dear Dan,

Thank you for the great replies.

Reply to Comment #1:

Regarding the idea that conditioning is always present ("the moment you practise techniques you are, in a sense, 'conditioning' the body"), I agree; however, as you noted the sine wave motion has removed some of that conditioning "load" from the patterns. For the ITF practitioner the patterns are not the exercise we turn to for dallyeon. If we want to condition our legs for kicks, for instance, we will practise kicks--slow kicks, fast kicks, individual kicks, multiple kicks, kicking combinations, leg drills, etc. Then combine them with other things into combos.

For conditioning we do different types of exercises (not mere gym style weight-training -- the photo may be misleading); of which a significant part is different types of drills, what you refer to as "dynamic context drills". They could be simple combinations like Grandmaster C. K. Choi's "Sparring Punching Drills" ( http://youtu.be/F66u7gvZuTk ) or much more complex, much more dynamic. There are solo drills (basically line drills and other combination drills) or partner drills. These drills, I believe, do for us what the forms do for you. They provide a dynamic context and all the rest. Also, these drills are less likely to include the sine wave motion to the same extend (if at all), as do the patterns. Again, I wish to underscore that while the sine wave motion is an important part of ITF and quite prominent in the patterns, it is not ever present or universally applied in ITF training. It has a time and place. For the ITF practitioner the patterns are an abstraction, in much the same way as pre-arranged sparring is an abstraction. (Compare with my essay on the Value of Pre-Arranged Sparring: http://sooshimkwan.blogspot.com/2010/12/prearranged-sparring-purpose-and-value.html ) In ITF different types of training are done on an abstraction-reality scale, from most abstraction (something like patterns or elementary level pre-arranged step sparring) to least abstraction, such as free sparring, traditional sparring, and so-called "reality based" self-defence training. Patterns, as a form of poetry in motion, has a very high level of abstraction for the ITF practitioner. For this reason, they are sometimes deliberately made concrete through "pattern interpretation" activities, in which we dissect parts of the patterns to create dynamic context drills (such as Colin Wee is apt at), or self-defence applications (such as Stuart Anslow is known for). However, such "pattern interpretation" activities is another type of training; they are not pattern training, in the strictest sense. (Or maybe this is the only true type of pattern training -- it all depends...)

Reply to Comment #2:

You mention that you "cannot see how sine wave could possibly improve your speed from the 'get go'." Notice, however, that I did not say that the sine wave motion improves speed. I said that the "interesting thing about the sine wave motion when correctly applied to natural stepping is that it actually creates forward momentum from the get-go just like the drop step". You may exclaim: "If it doesn't contribute to speed, why do it at all?!" Again, speed training for stepping is not to be found in the patterns. For the ITF practitioner the patterns are probably the least likely vehicle for stepping speed training; the ITF pattern tempo is much too slow for that. (Pattern training do support acceleration training, but I'll get to what I mean by that in a future post.)

You add that "In the tkd forms I've seen, the 'sine wave' is absolutely unlike, say, the 'drop step' of xingyi." I would agree that this is so, not because there are no similarities, but because so very few people perform the sine wave motion correctly! I may be ousted for saying this, but not even exceptional pattern performers like Jaroslaw Suska performs the sine wave ideally, because his purpose is tournament patterns. (Unfortunately, neither can I say that I've perfected the sine wave motion. It is really quite difficult to perform properly.) Your best bet to see it properly executed is to look at the North Koreans, and it was from such an instructor that I was taught the mechanics of the sine wave motion. (In fact, I was not a fan of the whole concept until I was showed how it works from Master Kim Jong-Chol.)

Also, a "natural step" and a "drop step" (as you define the two) are innately different because the one is an actual step -- one foot passes the other, and the other more of a "half step". When I say that the sine wave motion causes the natural step in Taekwon-Do to act like a drop step, I mean that the same principle of "controlled falling" (as someone once described Xingi) applies. The falling I'm referring to here is not merely the fall at the end of the sine wave motion, but peculiarly the "falling" at the beginning of the "relax-raise-drop" motion. It is that initial "relax" that initiates the forward momentum, even before the rear leg pushes. I'm not sure if you can visualize what I'm saying now; unfortunately I'm not going to explain it any further here, because this is the very essence of my planned future post on The Value of Patterns: Kinaesthetics.

Reply to Comment #3:

I have actually watched your video a while back already, shortly after it was uploaded onto YouTube in March. I found it quite interesting and educational.

Best wishes,

Sanko

Ps. I'm not writing about the sine wave motion on my blog for apologetic purposes. In other words, I'm not trying to be the Defender of the Sine Wave Motion, but rather an expositor--an "explainer". I don't see myself busy with ITF apologetics, but with ITF exposition. Considering how much I've written on the sine wave motion one may think that I am very passionate about the topic, when in fact I actually think overt focus on the sine wave motion causes myopia. The sine wave motion is really just one manifestation of the Wave / Circle principle, which is a much more important topic, I believe, that this singular manifestation. I write about the sine wave motion because I think it is a very misunderstood aspect of ITF Taekwon-Do, not because it is my favourite topic. My true interest is probably martial art philosophy--the martial art and martial way, rather than martial technique.

I suppose my point is this:

The type of conditioning needed for optimal stepping with techniques can only really be done in patterns. Gym work doesn't cut it. So for example, you could do all the gym, running etc. you wanted, yet you wouldn't be conditioned for tennis. To really understand what conditioning you need, you need to play for half a day and see what it does - even if you're supremely fit and conditioned in every other sense.

To be truly conditioned for melee stepping (including half steps) you need to practice those steps in a dynamic context. If not in patterns, then in something almost like patterns. Which poses the question, why not in patterns? Why7 waste this opportunity?

As to the sine wave adding adding a falling moment like a drop step - I agree. The problem is that it also requires a "load" for half the step - a load that occurs entirely during "dead time". In other words, you're grooving a load much like the "double hip". For what benefit? To gain more power? If your techniques mostly comprised downward moments (eg. stomping on someone who is on the ground), I might understand, but the vectors are largely horizontal. And as you know, downward moments only translate partially to horizontal moments.

Xingyi's drop step, as a matter of interest, is not geared at increasing speed nor power. It is merely increasing efficiency. Because in the end, civilian defence comes down to those microseconds. Forms in xingyi help you learn valuable kinaesthetics to avail yourself of the crucial advantage of that efficiency.

And it is worth noting that xingyi and bagua "forms" approximate karate and tkd "walking up and down the floor in basics". In other words, they are definitely not "fight plans". They exist purely to groove important kinaesthetics (which include being relaxed in movement).

Unlike you Sanko, I am an apologist for traditional martial arts! I've reconciled myself to that for some time. But like you, I share a deep and abiding love for the philosophy. If I didn't feel the sine wave wasn't heading in the wrong way technically as well as philosophically I wouldn't bother debating it! It's only when one sees how xingyi, bagua and taiji are physical embodiments of the Daoist classics that one appreciates the link between movement and form.

I admire your defence - and the spirit in which you do it! But for now, I remain unconvinced, though open to further persuasion!

Hi Dan,

I concur with you that “To be truly conditioned for melee stepping (including half steps) you need to practice those steps in a dynamic context.” In ITF that conditioning occurs only partially in the patterns. The real place where we drill in conditioning for the melee range is elsewhere: line drills, partner drills (dynamic context drills), and so on. My conviction is that the melee stepping grooving for ITF occurs partially in the same place it occurs in Xingyi. As you said, xingyi doesn't really have forms—in a Karatesque sense. Rather, Xingyi's “forms” are basically line drills, and this is where Xingyi grooves its melee stepping. In ITF this is also the place, line drills, partner drills, and so on, where this grooving takes place.

To this you respond: “Which poses the question, why not in patterns? Why waste this opportunity?”

Honestly, I don't know. I can only speculate. When ITF broke away from the Shotokan tradition and started doing continuous sparring, I think a whole shift took place in the ITF pedagogy. I think had there not been such an emotional investment in the patterns, Taekwon-Do may actually have abandoned them, and would have become something akin to Jeet Kune Do. What ITF is now, is something in betwixt—one foot within the traditional martial arts and one foot within the “modern” martial arts. Then in the 80s another major shift occurred, that dramatically changed the style. Up until the 70s ITF Taekwon-Do was undeniably a hard style martial art. From the 80s it became a strange hard-and-soft style. And it is still settling into this new hybrid, with people like myself embracing it, and others resisting it.

You rightly argue that: “If your techniques mostly comprised downward moments (e.g. stomping on someone who is on the ground), I might understand, but the vectors are largely horizontal. And as you know, downward moments only translate partially to horizontal moments.”

I agree, but it is interesting to note that most techniques (particularly strikes) in the ITF patterns are “middle section” techniques and in ITF Taekwon-Do most of these do not reach their target at a primarily horizontal vector, but at a somewhat downward angle. Body dropping is therefore appropriate. (That body dropping ads force in these cases is undeniable—how much force is added and how feasible these types of techniques are in the chaos of a real fight is speculative.)

About traditional martial art apologetics: I know you are and that is why I like reading your blog so much. For myself, I practise both in traditional martial arts (ITF Taekwon-Do, Hapkido and Taekkyeon), and in “modern” combat sports (e.g. grappling) and have focussed for a long time on self-defence (not martial art depended). However, my love is definitely with the traditional arts. Do I advocate traditional martial arts for self-defence purposes like you? No, not really. While I believe they could be excellent for self-defence purposes if taught and trained correctly, I think that in general they take too long to master. Most people wanting to learn self-defence do not have the time, emotional endurance and passion to devote to the traditional arts. There are many other benefits for which I would advocate traditional martial arts, self-defence (in the long run) being only one.

I appreciate your admiration of my defence. I'm not sure if I'll convince you, since my goal is to explain, not defend. As I said, I'm busy with exposition not persuasion. Also keep in mind that I am one voice in a global ITF community. I'm sure that there are many ITF people that do not agree with my take on things.

As always, I appreciate your discussions.

As I appreciate yours Sanko!

Well done again!

One story from Yang lineage based Taiji was that one master, one of the inheritors of the yang style lineage, told another person that he could make them take the shape of an iron ingot. He would then strike or push them in the stomach, and the force was such that the guy was launched horizontally as well as vertically backwards, forcing his pelvis back, and his legs and head forward, thus taking the shape of an ingot as he slide backwards along the dirt ground.

Such is the power (ideal or real) of internal Chinese martial arts.

If TKD, any faction even, wish to develop this power, they must study how it was done in the ancient days first. Before experimenting with modern equipment and applications.

I have seen modern renditions of R/D on this matter, but their information sources are perhaps not easily accessible to the average civilian or citizen. Sort of like a niche thing in the modern world, where information is more likely to overload than educate.

If a student of H2H wishes to accelerate a person's pelvis 45 degrees, over and down, then do they get that result with the sine wave? If they do not, either the sine wave is functionally non productive, or the student lacks certain skills to make things work.

Sanko is correct in noting that the benefit from the sine wave would impart forward momentum in similar kind to the drop step in Xingyi. While I would say that it is not enough forward momentum the way it is done, that is a difference in scale and magnitude, rather than in kind.

Xingyi, because it functions in direct lines, is often concerned about not letting the opponent get away by opening the range. That is another additional goal of the drop step. To always be in the face of the opponent, and always ready to jump and run forward to catch them and in the course of running and lunging after them, one immediately converts that momentum to an attacking drop step when the range is low enough. This is the goal, the standard, for xingyi stepping.

If you apply that to TKD, it then does not follow from the form of the sine wave. The form is thus divorced from the function. I've never really been concerned with how martial art styles in the world did things. I've chiefly been concerned with their goals and whether their training methods were consistent with those goals. Did their methods help them achieve such goals or did their methods conflict with such goals.

If the TKD goal is power, forward or downward, then they should adopt 100% the drop step seen in Xingyi.

Dan may be getting a little bit process orientated given his studies in internal Chinese arts. I'm much more Western in approach to problems and solutions, although I also value and appreciate the Process approach. When the process is paramount, then it becomes an all encompassing matter whether a person is doing this step or that step in this way or that. It's like spine alignment and muscle relaxation of the shoulders in Taiji Chuan. One could ask what the "goal" of such things are, but they naturally do not ask such questions. Their primary concern is the "process", the path to the goal, not the goal itself. This is often a foreign concept to external martial artists. So often times they forcibly make themselves think in terms of process alone, to improve their learning of those concepts.

Hi Sanko,

I had no idea it had become so busy over here!

I dropped a reply on Dan's blog before coming here, it might interest you.

I'm on your wavelength as regards most things sine-wave, though there are some intimations of difference that I think will make The Value of Patterns: Kinaesthetics very interesting reading for me.

keep up the good work.

Ymar said:

"If the TKD goal is power, forward or downward, then they should adopt 100% the drop step seen in Xingyi."

I think there is a great deal more to xingyi than its drop step - and that cannot be taken out of its context. Having said that, the general concept of the drop step can be adopted by TKD and I have made some comments on my blog that I'll repeat here. I would however caution against a wholesale change of every step to a "drop step". I think any such change is far too drastic. This is precisely at the root of the difficulty I have with the sine wave theory: it is a general theory used to make sweeping and drastic changes to an art.

Many people consider me to be "progressive" but in this respect I am really quite conservative: make small changes after great deliberation and scientific analysis - not wholesale changes based on one (flawed) observation about a "natural" sine wave pattern seen in normal walking, but then extrapolated to an exaggerated rise in every step in patterns for what is, at best, an uncertain result.

Here are my comments in relation to the drop step:

"If you are doing full, natural steps in patterns (rather than just the drop), then it is worth examining why you're doing them. As I've said, "loading up" for a bigger drop isn't a good reason - at all.

Personally I don't have a problem with full, natural steps despite the "dead time" they entail; I've found a good reason to do them (ie. conditioning by adding load to core muscles so as to learn how to move as efficiently as possible and without telegraphing). For more on this, see my article: "Why bother with stepping in stances".

I think that adding an "arc" to full, natural steps does not help; it does the very opposite. It takes away any possible reason for such stepping.

I suggest that if you want to exercise the second part of sine wave (ie. the fall) then do that on its own; a study of yori ashi or suri ashi from the Japanese arts will help. I'm sure there are Korean equivalents. Or you can study xingyiquan, bak mei, southern preying mantis, white crane or any number of Chinese arts where this kind of footwork occurs.

If you like to use a "rise" with your strikes (eg. by pushing off the floor) then by all means do the same; the above arts are chock-full of similar techniques.

If you absolutely must do a "down, up, down" motion, then make every part count:

Execute one technique to time with the "up" and another to time with the "down". Don't just march through the "down, up, down" for the sake a technique right at the very end of this sequence.

For an example of executing techniques contextually with a rise and fall, see the video embedded in this article."

The sine wave, irrespective of the use people have put to it or on it, is a very ambiguous issue. In terms of a teaching tool, I cannot grade it very highly. Nor can I grade it highly in terms of its technical proficiency in terms of upgrading one's technical skills or power generation.

Martial arts is just as much about passing on skills and knowledge as it is about being competent in doing. So even if Choi knew how to use it, the fact that his students do not, does not speak well of the theory itself, tested by time.

The principles of Xingyi drop stepping, meaning momentum generation and shifting, can be applied. The context is the problem itself. But Xingyi's context is slightly different because the problems it sought to fix were like, but not the same, as the problems TKD sought to fix.

In order to take what Xingyi is able to work, and move it into TKD, I would say a person must be able to "backwards engineer" xingyi power generation and momentum transfer, back into whatever style they are using.

And that takes a supreme level of technical and principle comprehension. Which is why beginners are not told to do such things... it would simply be a mental project, and if anyone tried to use the fruits of such a project, they'd probably get killed.

Hi Dan,

"I would however caution against a wholesale change of every step to a "drop step". I think any such change is far too drastic. This is precisely at the root of the difficulty I have with the sine wave theory: it is a general theory used to make sweeping and drastic changes to an art."

On the above comment you made: 1. Again I repeat that the sine wave motion is not universally applied in ITF Taekwon-Do. It receives great emphasis in the patterns and some of the elementary exercises, but less in other parts. It is used here for a very specific purpose, to teach certain concepts. 2. It has to be seen within the context of Taekkyeon where "poombalki" is their basic stepping, which involves some type of bobbing, bouncing footwork. 3. The patterns are busy with many other things, the least of which, I would argue, is focused combat training. (When a boxer is practicing rope skipping we do not chastise him because this is not realistic fighting training--we understand that what he is doing is contributing in other ways.)

A great week to you all!

Ymar,

"In order to take what Xingyi is able to work, and move it into TKD, I would say a person must be able to "backwards engineer" xingyi power generation and momentum transfer, back into whatever style they are using."

I think that ITF TKD is busy with Xingyi type momentum transfer, but it is only partially seen in the patterns--it is more generally practised in line drills and other dynamic context drills. It was for this reason that the first time I saw Xingyi I shouted out: "But that's ITF!" And I get similar reactions from other ITF instructors when I show them, for instance this video:

http://youtu.be/6coUVC5uUL0

Of course I do not believe the two arts are exactly the same; however, I think there are more similarities than maybe what Dan sees. Then again, what is available online of ITF (usually the patterns) do not demonstrate the similarities as much and the similarities become more prominent at higher levels of ITF. So unless you have spent some time in ITF, you may not get it.

Anything that priorities the straight path, the line from A to B, is going to look like Xingyi somewhat. That is what I have concluded.

It's not that everything needs to be a drop step. A drop step is just one application of the linear principle. Just one. But in learning the principle, it's a good idea to focus on one application. Not a 1000 techniques or 10 applications. Maybe 3 techniques to show how things are done with the drop step. 3 techs that use fine motor control the least.

For conditioning drills, I would not utilize the theory of the sine wave as my primary modus operandi. I would utilize a couple of other training methods that I've worked with or researched.

"On the above comment you made: 1. Again I repeat that the sine wave motion is not universally applied in ITF Taekwon-Do. It receives great emphasis in the patterns and some of the elementary exercises, but less in other parts."

In that sense, i would interpret that to mean it is used in the same fashion as the Karate Horse Stance Punching exercise used to teach in Japan once the Shotokan founder moved from Okinawan to Japan. People, to this day in America, still think that the horse stance punching is what they would do in a real fight. Punch right, pull the right hand back to the hips, punch left at the same time. They think the "rotation" is the "power generation". Well, that would be funny if it wasn't also sad... one student, he had one year of karate experience plus some aikido, said he didn't know the use behind that drill. So I told him. The rotation is not for power, but for structure so the wrist doesn't collapse at different ranges. The pulling of the hand back is when I trap somebody's arm in a deflection and I decide I'm just going to pull that arm back and use the attacker's momentum, while at the same time I clock them in the head or throat with my other arm. Because they can't move away and is off balanced, they eat a lot of the force of my strike and can't absorb it. I was kind of surprised by the fact that he literally jumped forward when I did the pulley pull. I didn't think I used that much strength. Maybe he was just flat footed. But it is rather ironic that I, without a single day in karate, ends up having to tell a karate student what the real stuff in his training was about. Better late than never, I suppose.

Of course, that's why I don't agree with the whole idea of the horse stance training. Not because it isn't good physical training, but because it inculcates bad habits mentally. At least, not unless the student is also told the correct theoretical mechanics behind it at the same time they are spending time on the reps.

I think Dan's point that there is some erroneous theory being attached to this kind of movement or drill, is on target. Which is why I would use other drill type movements to teach the concept of power generation, etc etc.

Post a Comment