In an essay I posted on the Soo Shim Kwan-blog in December 2020 I mentioned as a footnote the idea of postmodern martial arts. In

the middle of 2021, while on a martial arts podcast about that post, the

interviewer asked me about that postmodern martial arts comment. My answer on

the podcast was rather sparce because to answer such a question would really

require at least a cursory exposition of what Postmodernism is and only then

can one attempt to define what a postmodern martial art would look like. Since

our time on the interview was already coming to an end, I kept my response

brief. However, the postmodern topic again passed by my radar recently when in two

of my university classes this past semester I spent a few units on

Postmodernism. This made me think about postmodern martial arts again, so I

decided now might be a good time to ponder the topic once more—here in writing.

What is a Postmodern Martial Art?

by Dr. Sanko Lewis

Postmodernism

|

Image Source

Different modernist worldviews

promised utopias, but delivered

dystopian regimes. |

Let me begin with a brief—and very simplified—introduction

to Postmodernism. Postmodernism is a Zeitgeist (“spirit of the time”). Zeitgeists

are basically a ‘paradigm’ or ‘worldview’ and is detectible in the many ways

that it manifests in society, culture, art, and even technology. The postmodern

Zeitgeist emerged around the 1960’s out of an earlier Zeitgeist, known as Modernism.

The “post-” prefix in Post-modernism does not mean that it appeared

after the end of Modernism, but merely that it emerged after the start of

Modernism. Aspects of Modernism is still very much active today; nevertheless, Postmodernism

has become hugely prevalent in many aspects of society at large. Without going

into too much of the history of these Zeitgeists, let’s suffice to say that

Modernism promised Utopias but delivered the world wars and the exploitation of

natural resources. Against this background of the Holocaust and Hiroshima, a

cynicism and scepticism emerged which is at the core of Postmodernism. Put

simply, Postmodernism rose in reaction to the ideals and values of Modernism.

Some important postmodern themes are:

- the

questioning and doubting of Grand Narratives,

- the

breaking-down or crossing of boundaries and borders,

- decentralization

and discontinuity,

- and

recycling and repurposing.

These themes manifest in many ways. I will discuss the

themes and some of their manifestations as they relate to martial arts.

Premodern and Modern Martial Arts

However, before we do so, it is important to make a

quick distinction between premodern and modern martial arts.

|

Zhang Sanfeng observing

a fight between a snake

and a bird. |

Premodern martial arts are those martial arts that is

thought to have developed in “ancient times” and adhere to a premodern

worldview; for instance, the believe in an animistic force (such as qi),

esoteric tribal (i.e., in-group) knowledge, and techniques inspired by

phenomena in the natural world, such as natural cycles and animal behaviour. It

is often believed that the martial art and its “secrets” have been handed down

in a lineage from master to disciple over hundreds of years and numerous

generations. An example of a “traditional” martial art might be Taiji Ch’uan,

which adhere to the theory of qi-power, the natural cycles of yin

and yang, and the folklore of the Taoist monk Zhang Sanfeng who

witnessed a fight between a snake and a crane.

On the other hand, modern martial arts are based primarily

on a modern scientific understanding of motion (Newtonian physics) and the

human body (physiology and biomechanics). Techniques are sourced from what “works”

(although this is questionable), rather than handed-down secrets. That does not

mean that modern martial arts are not transmitted from one generation to the

next, but the relationship is one of coach and athlete, rather than traditional

master and disciple. Although ITF Taekwon-Do occasionally regresses to

premodern customs, as a whole, ITF Taekwon-Do is a modern martial art that was

deliberately modernized by its founder. There are no secrets only available to

the insiders; credibility through lineages has been replaced by certificates

from an international governing body; magic energy made way for Newtonian

physics, and poetic animalistic moves became standardized biomechanical techniques.

Both traditional martial arts and modern martial arts

place their faith in their chosen Grand Narratives. The term “Grand Narrative”

refers to a “big story”, i.e., a standard explanation, for how things work. The

Grand Narrative in premodern martial arts is the lineage and the inherited

tribal wisdom and associated philosopy. The ancestral line is the centre of the

system and what legitimizes the practitioner’s knowledge and skill. In the case

of modern martial arts, the Grand Narrative is often some form of technical

manifesto which is legitimized by a governing body. For example, ITF Taekwon-Do

has a technical manifesto known as the “Theory of Power” and the related canonical

technical explanations which provides a “scientific model” for the system. This

is in turn interpreted and supposedly updated by the Technical Committee of the

ITF (whether at a local governing body or international governing body level). In

theory the Technical Committee is (or ought to be) populated by people that are

highly experienced in the system and have relevant qualifications in, for

example, physical education, sport science, biomechanics, physiology, physics,

etc.

Both premodern and modern martial arts are structured

within boundaries. Premodern martial arts function as intangible cultural

artifacts—like traditional dances. The cultural context, such as an ethnicity, tribe,

village, or family is its boundary; it is what separates it from another

martial art systems. For instance, Taiji Ch’uan is a Chinese martial art that can

be differentiate into five (literal) family styles: Chen Family Style (i.e.,

the version of Taiji Ch’uan developed by the Chen family of the Chen Village in

Henan province); Yang Style; Wi Style; Sun Style; and Hao Style. Modern martial

arts often define their boundary by their specialization, such as being a

striking art or a grappling art, a combat sport or military close combat system,

and so on. Modern martial arts seldom claim to be “everything.” Both Judo and

Boxing are sports, but clearly within their own spheres: the one would not

claim to be a striking system nor would the other claim to be grappling system.

Although Taekwon-Do may have some throws and ground techniques, it is

ultimately a striking art. Similarly, Brazilian Jiu-jitsu may have some

techniques from a standing position, but it is on the ground where it comes

into its own.

Postmodern Martial Arts

With the preceding context we are ready to dive into

the notion of postmodern martial arts. I will propose three examples of

postmodern martial arts: Hapkido, Jeet Kune Do, and what has become known as mixed

martial arts. And I will discuss each of these in relation to the

postmodern themes that I outlined earlier.

Hapkido

Hapkido is a modern martial art in the sense that it is

one of the “modern” systems that developed in the early 20th century

out of a premodern heritage.

|

| Choi Yong Sul, the "founder" of Hapkido |

During the Japanese occupation of Korea, a young boy

named Choi Yong Sul was taken to Japan. There he became a house servant to

Takeda Sōdaku, the founder of Daitō-ryū AIki-jūjutsu. At the end of the

occupation, Choi returned to Korea and started teaching what he called, among

other names, “Yusul” (the Korean rendition of “jujutsu”). As the system

evolved, so did its name, and eventually the name “Hapkido” became most

popular. While originally based on a Japanese system, Hapkido has evolved

dramatically. From early on, techniques that are foreign to the original Daitō-ryū

AIki-jūjutsu, such as an extended arsenal of kicks-and-striking techniques, were

incorporated from various local (Korean) and foreign martial arts. Hapkido also

developed numerous weapon systems influenced from local and foreign, such as

Chinese and Japanese, systems. Hapkido is a discontinuous martial art—a

bricolage of techniques repurposed from various systems; i.e., “crossing of

boundaries and borders”. Additionally, Hapkido still adhere to aspects of

premodern martial arts, such as the concept of qi (known as “gi” in

Korean) that features centrally in Hapkido’s technical philosophy and practice.

Yet it is also acts like a modern martial art—claiming to be a self-defence

system based on a technical manifesto of Newtonian physics and biomechanical

principles.

At first, Hapkido adhered to a strong lineage starting

with Choi Yong Sul, but by implication connected to Takeda Sōdaku and his Japanese

system. However, Hapkido quickly reimagined itself as a Korean system, and

incorporated not only Korean techniques but also Korean philosophical concepts.

The lineage with Choi Yong Sul is still acknowledged but as of today there are

over 60 governing bodies in South Korea alone, making it very much a fragmented

system. It is not a surprise, then, that the technical syllabi are practically

unique from school to school, with little standardization worldwide.

Most Hapkido schools present themselves in the way of premodern

martial arts with a long lineage, a particular ethno- and cultural quality (i.e.,

Korean), a master-disciple pedagogy, and even qi-cultivation techniques.

However, these elements are questionable, and may rather be understood from the

postmodern theme of “recycling and repurposing.” It is difficult to say to what

degree Hapkido is Japanese, rather than Korean, not to mention the

incorporation of techniques from other systems such, for example, Sambo

(Russian wrestling) and various Chinese styles. The master-disciple pedagogy of

tribes and villages is not how Hapkido is taught today—rather, Hapkido schools

are mostly often businesses and the students are clients. And it is not quite

clear how many instructors actually believe that qi is essential to

Hapkido techniques. In many Hapkido schools the idea of qi and even qi

exercises such as abdominal breathing exercises, often performed at the

beginning or end of a class, seem more to be an addendum than truly part of the

system. Techniques are better explained through physics, biomechanics, and

physiology rather than Taoist principles.

Jeet Kune Do

Jeet Kune Do is the martial philosophy of Bruce Lee.

|

Apart from martial arts, Bruce Lee

was also a cha cha dance champion.

Image Source |

Lee’s family was involved in Cantonese opera, which

includes various disciplines ranging from acting to singing to martial arts.

Hence, Lee was exposed to these performing arts and even performed in some

rolls as a child. While in school, Lee learned boxing and as a teenager he

started learning Wing Chung Kung Fu under a grandmaster of the style Yip Man,

who claimed to be part of the direct lineage to the Yim Wing-chun after whom

the style was named. Lee also added the Cuban dance cha-cha-cha to his

extracurricular activities. Lee relocated to the United States where he started

to teach martial arts—basically his version of Wing Chun, but here Lee would be

exposed to various other martial arts. For instance, Lee learned Taekwon-Do

kicks from Grandmaster Jhoon Rhee (father of Taekwon-Do in the USA).

In 1964 Lee had a fight with a Chinese martial artist,

Wong Jack-man, in Oakland, California. According to Lee the reason for the dual

was because he was teaching martial arts to “outsiders” (i.e., Americans),

which was not allowed by the Chinese community. Although Lee claimed to have

won the fight, he was disappointed with his performance and concluded that his traditional

martial art skillset was too formalized and, hence, limiting. This led to a

journey of abandoning tradition for what he called a “style of no style.” His

goal was not to create yet another system of fixed techniques, but rather a

“philosophy” that embraced the idea of “using no way as way”; i.e., not being

limited to any particular martial system but rather incorporating whatever

works from any system, based around a number of technical and strategic

principles such as efficacy and interception.

|

| Bruce Lee learned Taekwon-Do kicks from Jhoon Rhee |

This exemplifies the postmodern questioning of Grand

Narratives. Lee questioned both tradition and lineage (“discontinuity”) and

started to research and incorporate other martial arts into his system,

including those of European origin such as European fencing and savate (a

French martial art). Thus, Lee manifested another postmodern theme: “the

breaking-down or crossing of boundaries and borders,” which he was also doing,

according to his account, by not only learning from other cultural systems but

also teaching “outsiders”. Sourcing from different martial arts also

exemplifies the postmodern theme of “recycling and repurposing.” Bruce Lee was

clearly a postmodernist, and his methodology was one of deconstruction. Lee

named his approach Jeet Kune Do.

Today, many people who practise “Jeet Kune Do” are not

doing it as a postmodern philosophy. Rather, they have reverted to premodern martial

arts notions of lineage and other fixed training methodologies. Nevertheless,

there are still people who follows Lee’s postmodern “way of no way”.

Mixed Martial Arts (aka Hybrid Martial Arts)

As the name suggest, mixed martial arts are

literally the result of sourcing skills from different martial arts to form a

hybrid or eclectic system. In other words, it is the individualized practice of

mixing techniques together, often to create a personalized “rounded” skillset

that can defend at different spheres of engagement: striking, clinch, and ground.

One might combine Boxing, Taekwondo, and Judo; or Muay Thai and Brazilian

Jiujitsu; or any other combination.

This mixing of styles from different systems and even

different cultures is a manifestation of the “crossing of boundaries” theme in

Postmodernism. Furthermore, as there is no respect for an actual ancestral

lineage nor a true governing body, mixed martial arts is essentially

decentralized. Practitioners can jump from one school or system to another at

whim as soon as they have “collected” a skill or technique that they wish to

add to their skillset collage. Mixed martial arts training is discontinuous in

nature—this doesn’t mean that the practitioner is not continually training, but

simply that they are not necessarily loyal to a continuous lineage as is the

case with premodern martial arts or the dedicated specialization in modern

martial arts. There is a scepticism in mixed martial arts that questions the

validity of traditional (i.e., premodern) martial arts as well as the myopic

focus of the modern martial arts, but when valuable techniques or skills are

identified, they are dislodged from their original context and repurposed to

the new non-traditional context.

A sport known as “Mixed Martial Arts” (MMA), epitomized

by the UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship), has emerged. This sport is

in many ways similar to modern martial art combat sports—it is nevertheless

postmodern in its mixing of a serious sport with the pomp and pageantry of the

entertainment industry.

Embracing a Positive Postmodernism

I’m certain, that many martial artists would feel

offended if I were to say that their practise is postmodern or even that they

could benefit from being more postmodern in their training. For many people,

Postmodernism has become a swear word, often associated with Relativism and

Nihilism; hence they associate anything “postmodern” with meaninglessness.

Unfortunately, this is due to a common misunderstanding and inadequate

understanding of Postmodernism. It is not the case that Postmodernism is anti-truth,

as is often claimed. Postmodernism’s protest of Grand Narratives does not mean

that there is no truth, but rather that reality is too multifaceted to be

explained by a singular framework (i.e., one Grand Narrative).

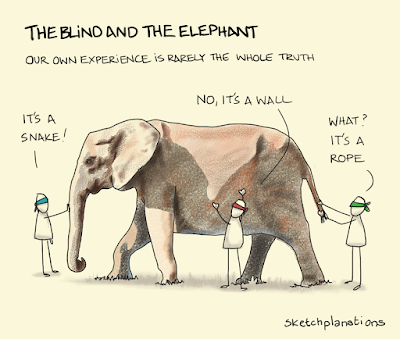

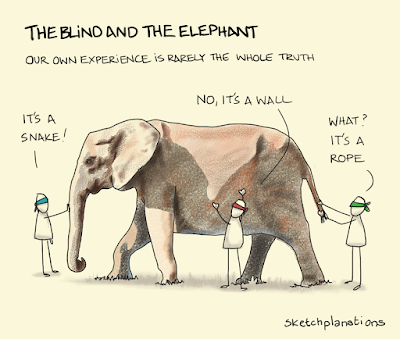

|

The parable of "The Blind and the Elephant"

exemplifies the postmodern understanding of truth

that is approximated through different points-of-view.

Image Source |

A postmodern pursuit of knowledge is one that allows

for many points-of-view. In martial arts terms we may call it “cross-training.”

It is the realization that there is no ultimate martial art, but rather that we

can learn from many martial arts. And in fact, it is such an ability to view

the world from different points of view that brings us closer to reality. As

such, simple “cross-training” is not enough. For instance, mixed martial arts

are postmodern in their cross-training, but they are often spiritually superficial,

as they still tend to cling to singular goals, such as a modernist ideal of winning at all cost. Mixed

martial artist could benefit from expanding their “cross-training” to other “spiritual”

disciplines such as finding ways to include a “spiritual discipline” or “moral

culture” or even meditation in their training so that they don’t just train how to fight, but also

pursue becoming better human beings (goals often pursued within premodern martial arts). It is here then where I want to connect this essay

with the essay which I wrote just over a year ago on “Pre-Rational, Rational, Trans-RationalViews of Martial Arts”.

It is my conviction that there is value in becoming

transmodern martial artists that incorporate the best of both premodern and modern martial arts paradigms and develop systems that are truly beneficial at various levels. I believe that one can do this within existing systems or individually within one’s personal martial arts journey. It requires, however, honesty, humility, and open-mindedness. Honesty to admit what doesn’t work within your

system; humility to learn from other people and other sources; and open-mindedness to explore the unfamiliar.

I do make a distinction between simply a postmodern martial artist and a trans-modern martial artist. The former can easily become haphazardly fragmentary, without any over arching cohesion. Or, simply busy with deconstruction* without reconstruction. However, if the postmodern journey is a positive one, where the deconstruction is also generative, then it may be of the trans-modern sort: a creative journey of development that synergistically brings together principles and ideas across various styles and disciplines to create something deeper and richer.

*Deconstruction

is a postmodern methodology for analyzing the underlining assumptions and

contradictions within a system.