This year I haven't had much time to contribute to the Soo Shim Kwan blog. Practically of the posts were material I prepared for academic purposes such as academic articles, conferences and symposiums. However, before 2020 comes to an end, I decided to write one essay. I'm guessing that this essay may rub some people the wrong way, but I think the concepts are very useful and will hopefully help some people in understanding the martial arts better.

Pre-Rational, Rational, Trans-Rational Views of Martial Arts

By Dr. Sanko Lewis

I sometimes

find myself bumping heads with rational people over certain aspects in

Taekwon-Do because they seem to think my acceptance of some elements of Taekwon-Do

is an irrational clinging to tradition or a cult-like following of the principal

founder of Taekwon-Do, Choi Hong-Hi. I came to realize that there is a

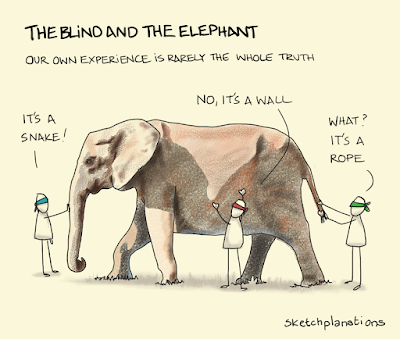

Pre/Trans fallacy at work. Therefore, for this essay I want to explore three

paradigms for understanding martial arts, which we can name Prerational,

Rational, and Transrational paradigms. We may also name these paradigms Premodern,

Modern, and Transmodern. I

will apply these respective terms (Prerational:Premodern; Rational:Modern; Transrational:Transmodern)

interchangeably.

An

understanding of these three paradigms may help us to clarify and distinguish

between various martial arts systems and the work of martial arts instructors

and scholars.

Prerational

Martial Arts, i.e. Premodern Martial Arts

Prerational

martial arts—specifically within the East Asian martial arts context—are those martial

arts that we usually group under the heading of “traditional” martial arts. These

martial arts often have an exceptionally long historical claim, with a mythical

or legendary origin or founder. Instructors’ authority is based on an unbroken

lineage and their knowledge is supposed to be the accumulated wisdom passed

down from one generation to the next, from master to disciple. Such martial

arts claim to possess “secret” knowledge, secret techniques, maybe even secret

manuals, that was passed down from the previous generation to only the most

deserving disciples. The forms (patterns) are often believed to contain hidden

or secret techniques that are only known or understood by the initiated. Thus, prerational martial arts may be defined as esoteric.

These

martial arts’ pedagogies are often not very structured. Generally, there are no

clear ranks (i.e. grades or belts). Rank distinction is very rudimentary. There

is the master and his or her disciples, and the students’ seniority is based on

their length of study and loyalty. In the most traditional systems, before a master dies,

he would appoint his successor—usually the most loyal and longest studying

student, who it is believed have learned everything the master knows, including

the system’s secret knowledge. Premodern martial arts are also often tribal,

believing their system is the best and other systems are weaker since they do

not share the same secret knowledge. Not surprisingly, there tends to be a distrust of outsiders.

A Chinese painting from the 2nd Century BC,

depicting Qigong (Doinsul) exercises.

Often, the

theories of power in these premodern martial arts are based on an animistic worldview, such as Daoism (China) or

Shintoism (Japan). Animism refers to a belief that everything (from stones to mountains to

people) is permeated or animated with a life force or spiritual energy. In East Asia this life force

is known as 氣 [Qi (Chi) in Chinese,

Gi in Korean, and Ki in Japanese.] It is believed that humans can manipulate 氣 through certain training such as

Qigong (China) or Doinsul (Korea). By cultivating and manipulating 氣, the

practitioner can improve their own health and increase their physical strength—even,

acquire supernaturally powerful martial arts techniques. 氣 cultivation training often involves

meditation and/or breathing exercises, particular poses, and pose sequences

(forms or patterns). Furthermore, if one knows the secrets, one can also

inhibit the life force in your opponent, for instance through the striking of secret

points on their body to create energy blockages. It is important to note here

that these prerational martial arts are not necessarily ignorant of physics and physiology,

although such knowledge is sometimes based on outdated scientific models.

Premodern martial

arts are also known to include other quasi-religious teachings. The

martial art is often used as an ascetic discipline for spiritual development. Thus,

the martial art is viewed holistically. It is not just about learning how to

fight, but also a means to better health, moral growth, and spiritual

enlightenment. The student is an apprentice and disciple, and the instructor is

a skilled artisan and spiritual teacher.

Rational

Martial Arts, i.e. Modern Martial Arts

Jigoro Kana, the Founder of Judo, and pioneer of modern martial arts

The degree

to which the label “rational” applies to different martial arts differs, since

many rational martial arts also include some prerational elements because modern

martial arts usually developed out of premodern systems. Rational or

modern martial arts are those that developed during the 20th century

and culminated in MMA in the 21st century. Probably the earliest modern

martial art is Judo, which was created by Jigoro Kano in 1882. Kano had a

Western education and it is believed that this greatly influenced his

systematizing of Judo’s pedagogy. He was the first to introduce a belt ranking

system in the martial arts. Most of the martial arts that developed in the 20th

century such as Taekwon-Do, Jeet Kune Do, and even kickboxing may be considered

rational or modern martial arts.

Modern martial

arts instructors’ get their authority from governing bodies (organizations)

that certify their rank. Techniques are generally explained, not through lineage,

philosophical metaphors, or esoteric notions of energy, but Newtonian physics

and biomechanics. Research in Physical Education and Sport Science are embraced

to enhance the athletes’ performance. In fact, the martial art is often

streamlined to a singular focus, such as combatives (e.g. Krav Maga) or sport

(e.g. Judo, WT Taekwondo).

Probably

the pinnacle of modern martial arts is Mixed Martial Arts. MMA has nearly

completely thrown-off its obligation to lineage and tradition. Techniques are

aggregated from many different martial arts based purely on their efficiency

within the MMA ruleset (most notably the UFC). Techniques are explained by

means of a Western scientific understanding of physics, biomechanics, and

sports physiology. There is no ascetic goal or focus on spiritual growth or

development of the character. Instead, the focus is to become a better

“fighter” (i.e. athlete), physically and technically.

Rational martial

arts tend to reject and look down on prerational martial arts, viewing them as

useless, outdated, and superstitious or fake.

Trans-Rational

Martial Arts

For this

section on transrational martial arts, I am going to talk more about transrational

martial artists in particular, rather than transrational martial arts in

general. The reason is there are very few martial arts systems that as a whole

can be considered transrational because most practitioners within these systems

are often blends of Pre-Rational and Rational.

Transrational

refers to a transcendence (and inclusion) of the rational. It is the ability to

use the rational, without fully rejecting everything that the prerational

represent. It is an ability to re-investigate the prerational and reinterpret and

re-apply premodern ideas and techniques from a new paradigm. Note that the transrational

practitioner is not a blend of Pre-Rational and Rational, but a transcendence

of both. I will provide some examples later which will help to clarify the

distinction.

Applying

these Paradigms to Taekwon-Do

To make

these concepts more tangible, I will now apply these paradigms to (ITF) Taekwon-Do.

Taekwon-Do

developed in the 20th century. It was built on a foundation

inherited from mostly Shotokan Karate which in turn came out of prerational martial

arts. However, from the start, Taekwon-Do based its teachings on Newtonian

physics. In all 15 volumes of the ITF Taekwon-Do Encyclopaedia, there is only

one short passage referring to 氣

(“Ki” / “Chi”), and not

within the context of power generation. Power generation is understood through

such equations as Force = Mass x Acceleration or Kinetic Energy = ½ Mass

x Velocity².

Even the language

has been demystified. Nearly all terminology has been stripped of their poetic

and metaphoric nuance. There are no techniques with names like “monkey steals peach”, “pulling the tiger’s

tail”, or “silk reeling”. Instead, techniques are conspicuously

descriptive: front punch, side strike, low block, back kick, joint break… There is no

“secret” knowledge in Taekwon-Do that are only available to the grandmasters. At

a technical level, Taekwon-Do instructors are simply coaches that help the

practitioner achieve their athletic goals.

Taekwon-Do

is a modern, rational martial art; however, occasionally we can find some

prerational / premodern aspects within Taekwon-Do.

Considering

WT / Kukki Taekwondo for a moment, the idea that Taekwondo has a 2000-year

Korean history is still propagated by some members of World Taekwondo and the

Kukkiwon. Even though this 2000-year history narrative has been thoroughly debunked,

there are still people who cling to this notion because such a long lineage

claim provides a sense of legitimacy. (And it sidesteps the inconvenient truth

that Taekwon-Do has its roots in a Japanese martial art.)

While ITF

Taekwon-Do has thankfully not taken up this untruth, there are nevertheless

people with similar prerational views within ITF. One example is the unwavering

loyalty to the Choi bloodline and lineage proximity to General Choi Honghi, who

was the principal founder of Taekwon-Do and first president of ITF Taekwon-Do. There

are some people within ITF who are obsessed with their lineage proximity to

General Choi; in other words, the idea that if you trained directly under

General Choi or if your instructor trained under General Choi, then your

Taekwon-Do is more legitimate than someone who is a third or fourth or later generation

practitioner. Before General Choi passed away, he appointed North Korean IOC

member, Chang Ung, as his successor. Dr. Chang Ung was succeeded by Grandmaster

Ri Yongson. Some people are of the opinion that those who do not follow this

lineage are not really doing authentic ITF Taekwon-Do. Similarly is the idea

that there is “magic” in the Choi bloodline; the notion that General Choi’s

son, Grandmaster Choi Junghwa, is the only true embodiment of Taekwon-Do and

that people who are not following him are not practicing true Taekwon-Do. Now

don’t get me wrong, I’m not disrespecting General Choi or the Choi-family,

I’m just pointing out that this type of thinking is prerational and tribalistic.

One is definitely able to practice real ITF Taekwon-Do—and be great at it—even if

you have never trained directly with General Choi or Grandmaster Choi Junghwa.

You can also be a true practitioner of the ITF system, even if you are not

affiliated with any of the mainstream ITF branches. There is no magic in the lineage, bloodline, or organization. General Choi broke with that prerational lineage notion when he

made it clear that Taekwon-Do is a new invention based on Karate and a few

other sources and by teaching Taekwon-Do not to a few selected students, but

all around the world to anyone willing to learn. There are no secrets passed

down to a select few. Taekwon-Do has been democratized. Anyone may have access

to the Taekwon-Do knowledge as provided in the ITF Encyclopedia and other

sources.

A further

example of prerational martial arts thinking you may have come across are those

people who search for “secret” applications from the patterns and go through

great pains to show applications from the patterns—sometimes the applications

are ridiculously contrived but they are presented as “hidden” discoveries.

Rational martial artists often fall into this trap because they want to explain

the inclusion of the patterns within the system in a rational way. They want to

legitimize the training in patterns, since it is so obvious that the patterns

are unnatural and do not reflect actual combat.

Another

example is the ‘sinewave motion’, which is a teaching aid that conveys a number

of useful principles, which I will simply reduce to (1) as far as possible

begin each movement from a state of relaxation, (2) accelerate all of your body

mass in the direction of the technique, (3) when possible move with gravity. Apart from these technical functions the ‘sinewave motion’ also have a cultural funtion; it provides a Korean cultural

character to the techniques by including Korean Body Culture elements such as ogeumjil 오금질 (knee-bending / knee-spring), three-beat rhythm, gokseonmi 곡선미 [曲線美] (Korean

curved line aesthetics), etc. Unfortunately,

there are some people who consider the ‘sine wave motion’ in a prerational manner

as a “secret” or “magical” way to increase power. They use it as a tribal

identifier to look down on other martial artists who do not know and use this

“secret” method. Also, they often apply the ‘sinewave motion’ not as a teaching

aid to convey certain principles of movement, but in all contexts even when it

would be illogical to do so. For instance, the full ‘sinewave motion’ contains

a relaxation, rising, and execution or falling phase, often mnemonically

chanted as “down-up-down”. Doing the falling phase during an upward technique

such as a high punch is counterproductive, nevertheless, these practitioners

apply the ‘sinewave motion’ in a blanket fashion to nearly all techniques.

Tribal premodern thinking is also evident when certain organizations prohibit their members to train with non-affiliated members (i.e., “outsiders”) or prohibit them to compete in tournaments or participate in seminars of other organizations. Nearly a decade ago, a friend and I who both practice ITF Taekwon-Do and Hapkido used to train together. At the time, we could freely train Hapkido together, but not Taekwon-Do because the ITF organization he belongs to did not allow members to train with “outsiders.” One would hope that such tribalistic and esoteric thinking would be something of the past; however, I heard of a recent case where one ITF group expelled a master who opened his private seminar to members outside of the ITF group he was affiliated with.

Moving on,

I believe, based on General Choi’s continual evolution of his system, that

Taekwon-Do was intended not to be simply a rational martial art, but rather a

transrational martial art. Rational martial arts, as I mentioned before, are

usually myopic. They tend to have a single focus such as competition or combat

exclusively. MMA as exemplified by the UFC or Krav Maga are such examples. At

the very beginning, even General Choi viewed his new style in such a manner—primarily

as a combat system for the ROK military.

Like the

holistic prerational martial arts, transrational martial arts also acknowledge

that the martial arts may have many different goals. ITF Taekwon-Do is foremost

an “art of self-defence,” but it can also be a means to improve health and develop

character, be a recreational sport, a way to promote Korean culture, and even a

soft diplomacy tool. In his further development of Taekwon-Do, General Choi

started to include these and other goals for Taekwon-Do. Instructors are

therefore not reduced to sport coaches only, but to life coaches—and based on

the ITF Taekwon-Do terms for instructors, they are conceived as teachers of moral wisdom.

Rather than

disregarding everything prerational as irrational, as proponents of rational

martial arts tend to do, transrational martial artists revisit prerational

aspects and reinterpret them from a new enlightened vantage point. Meditation

and danjeon-breathing are a common part of prerational martial arts,

which is often disparaged by modern martial artists because these breathing

exercises are part of the 氣-development curricula of premodern martial arts. Transrational martial artists, however, are

aware of the contemporary scientific research on the numerous benefits of

meditation practices such as visualization for performance enhancement, mind-training for focus, and conscious breathing techniques (aka “breathwork”) that can be used to achieve

various physiological and psychological states.

The

patterns are similarly upcycled by transrational martial artists. The patterns

are not viewed as 氣-cultivation poses, as in the case of prerational martial arts, nor do they

pretend that the patterns are combative manuals as sometimes happen with

rational martial arts. They accept that the patterns are cultural artifacts

inherited from the prerational martial arts and has value as part of the

intangible cultural heritage of the system. Transrational martial artists are

honest about the fact that patterns do not reflect real fighting and that we do

not fight like we do patterns. Instead of trying to derive hidden secret applications

from the patterns, transrational martial artists rather use the patterns in a

more general way to teach certain movement principles or use sequences of the

patterns as inspiration for dynamic context drills. Note this is different from

searching for secret or hidden applications, because generally these secret-technique

hunters try to find specific applications for a movement sequence. Whereas, applied

to dynamic context drills, these sequences are used to find combative or

tactical principles, rather that specific applications. A

good example of someone who use the patterns in a transrational way is Master Colin

Wee. Transrational

martial artists will also employ the patterns for purposes beyond combat; for

example, the patterns are great for suhaeng 수행, a type of movement meditation

practice.

Moving on

to the ‘sinewave motion’: instead of seeing the ‘sinewave motion’ as bad

science, as so many of the modern martial artists do, transrational martial

artists understand that the ‘sinewave motion’ is simply a tool for teaching

particular principles about movement and Korean culture; and they use these

principles not dogmatically but as they are situationally apt.

Pre/Trans Fallacy

At the

start of this essay, I mentioned the Pre/Trans Fallacy. This fallacy occurs

when rational martial artists mistake transrational martial artists as

prerational. The problem is that transrational martial artists

sometimes use the practices, terminology, and metaphors of the prerational

system. Rational practitioners have a knee-jerk reaction to this, and then

simply dismiss transrational instructors as prerational. The difference between

prerational martial artists and transrational martial artists is vast. When a transrational

martial artist use aspect from prerational martial arts, they do so from a

completely different paradigm. They are not working from a prerational “magic”

paradigm, but from one that is rational and open-minded. They view the martial

arts in a broader context, for instance not simply as a means for fighting but

as a tool for enhancing individuals’ lifes and affecting society—informed by

modern science, personal experience, and cultural awareness.

For

example, I am an ITF Taekwon-Do practioner who performs the ‘sinewave motion’ during

patterns. When someone tells me that what I’m doing is “too slow” and will

never work “in the streets” I can only shake my head. This is obviously a case

of Pre/Trans Fallacy. I know full well that it is too slow and that doing such

a block/punch/kick sequence is not reflective of actual fighting. I don’t

perform patterns because I think ‘it’ is ‘reality’. There are many other

valuable reasons for training in the patterns and doing the the ‘sinewave motion,’ which I have written about extensively elsewhere on my blog. And truth

be told, I’ve come to realize that doing the patterns simply because they connect

me with an intangible cultural heritage is of value in and of itself. (Although

I definitely think that there is useful skill transfer when the patterns are

properly employed as part of a sensible pedagogy.) Similarly, I am aware that General Choi Hong-hi was a flawed man, so I do not venerate him in a cult-like manner, as so many ITF practitioners do. Nor do I participate in contemporary “cancel culture”, which is an approach followed by many non-ITF people. Instead, I am appreciative of the great legacy of General Choi Hong-hi and other Taekwon-Do pioneers and as a martial art scholar I try to objectively contribute to correcting the narratives with regards to the history of Taekwon-Do. In this sense, I have an appreciation of lineage and those that came before me, without having an unhealthy obsession with it.

Take

Away

I should add here that I don’t mean to say that there are no applications for

pum [i.e. movement sequences] in the patterns. There often are and it may be

useful to teach them to students as long as they are mostly obvious rather than

contrived applications. However, an obsessive search for “secret” or “hidden”

techniques are a sign of prerational martial arts thinking.

Joong Do Kwan Taekwon-Do, Perth, Australia. http://www.joongdokwan.com/

[5] Some recommended resources you can start with are Steven J. Pearlman’s The Book of Martial Power, Jason Thalken’s Fight Like a Physicist, Jung K. Lee’s The Science of Taekwondo, Larence Kane and Kris Wilder’s The Little Black Book of Violence, and Rory Miller’s Meditations on Violence, to name just a few. The Combat Learning Podcast by Josh Peacock is also a great entry into methodologies of effective training based on Physical Education and Sport Science research.